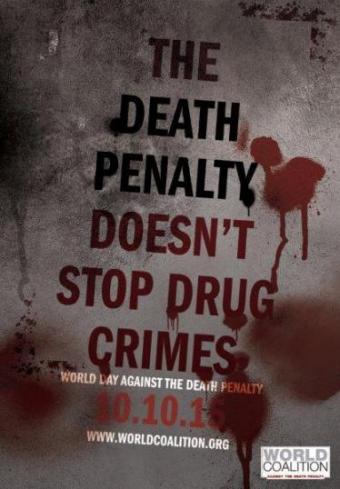

Drugs and Judicial Deaths Iran : World Day Against the Death Penalty Oct.10

World Day Against the Death Penalty Oct.10

World Day Against the Death Penalty Oct.10

Siavosh Jalili

September 2015

To anyone following Iran’s human rights news in recent years, the surge of executions has been on top of the list of human rights violations committed by Iranian authorities. Radio Zamaneh reports that in the first 9 months of 2015, 791 individuals have been executed. A large part of those executed (49%) have been convicted of drug-related charges . It is safe to assume that some of those executed were not really guilty of any drug-related charges: There are two examples that highlight such injustices:

1. The cases of Zahra Bahrami who was hanged in January 2011 on the charge of trafficking cocaine while she was initially arrested for taking part in post-2009 election protests

2. The recent case of a teacher, Mohammad Ali Barati, who was executed on the charge of trafficking drugs. The only evidence against him was the allegedly false confession of a man who had sold drugs to Mr. Barati’s brother who is also on the death row. The man in question, also executed, had recanted his confession.

While the above cases point to appalling instances of human rights violation it appears that a majority of the defendants were, in fact, trafficking, or at least in possession of, narcotics.

Draconian, Deadly Drug Laws

Iran has some of the most draconian drug laws in the world, and it is one of the 32 jurisdictions with capital drug laws sharing the company of such countries as China, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia in that category.

Various sections of Iran’s Anti-Narcotic Act prescribes automatic and mandatory death sentence for possession and trafficking of narcotics. Here is a list of some of the offences for which the Act prescribes the death penalty:

• Fourth conviction on the charge importing, producing, exporting, dealing, selling, and carrying narcotics

• Trafficking more than 5 Kg of hashish or opium, and opium by-products (residue, juice)

• Repeated conviction on possession of more than 5Kg of any narcotics

• Trafficking or possession of more than 30 grams of heroin, cocaine, codeine, methadone, morphine or any chemical extract of hashish

o The court could commute the sentence to life imprisonment if the defendant is a first time offender

Section 2 of Article 6 of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights to which Iran is a signatory states that “In countries which have not abolished the death penalty, sentence of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes in accordance with the law in force at the time of the commission of the crime…”.  The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Christof Heyns, has noted that “international law requires that [death penalty] may be imposed only after proceedings that met the highest level of respect of fair trial and due process standards. The ‘most serious crimes’ provision further requires that it is imposed only for the offence of intentional killing” .

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Christof Heyns, has noted that “international law requires that [death penalty] may be imposed only after proceedings that met the highest level of respect of fair trial and due process standards. The ‘most serious crimes’ provision further requires that it is imposed only for the offence of intentional killing” .

As recently as last week (March 12th, 2014), a group of independent United Nations human rights experts underlined that execution of drug offenders in Iran is “in violation of international legal provisions limiting the permissibility of capital punishment to the ‘most serious’ crimes” .

Another factor that makes Iranian anti-narcotics law particularly harsh, and even unfair, is that in most cases, there is no distinction between “possession” and “possession with intent to sell”. In most legal systems, the former is considered a less severe offence, and some room for leniency is left for those possessing the narcotics for personal use.

Lack of Due Process

Iranian legal system has predicted due process for most offences. Whether this process is followed is another question. However, as we will see below, for the capital drug offences, not even a semblance of due process exists.

Consider the legal process for an individual charged with (and in this example convicted of) murder. For the sake of the argument, we disregard the fact that defendants are often tortured during initial interrogations, and give the judicial system the benefit of the doubt.

1. The suspect is arrested and charged.

2. The lower court is held, and the defendant is found guilty and sentenced to Qesas (an eye-for an eye, i.e. death)

3. The defendant appeals the sentence

4. The conviction and sentence reviewed by an Appeal Court. The sentence is upheld.

5. The defendant appeals to the supreme court

6. A branch of supreme Court reviews the case and uphold the conviction

7. The defendant appeals to the Commission of Clemency and Forgiveness that would try to arbitrate between the defendant and the family of the victim trying to convince the latter to opt for blood money and spare the life of the defendant

8. If all appeals fail, the defendant appeals to the head of Judiciary. If he rejects his appeal, the sentence is sent to the Execution of Sentences circuit to be carried out

9. The defendant has one last chance to plea with the family of the victim to spare his/her life at the gallows

While this system is far from perfect, it provides the defendant with some reprieve. It is true that the Iranian authorities in more than one case have “expedited” the process or have interfered with the process to ensure the execution of the defendant. However, the room for pleas and appeals are open.

Now consider section 32 of Iran Anti-Drug Act:

“The death sentences issued by virtue of this Act shall be final and enforceable after the endorsement of the Chairman of the Supreme Court or the Prosecutor General”

In other words, once a lower court sentences a defendant to death on drug charges, (s)he has only one avenue of appeal: Chairman of the Supreme Court or the General Prosecutor. Islamic authorities in Iran have practically deprived all narcotic defendants facing the death penalty from fair due process of the law. Faced with ultimate punishment, most defendants are at the mercy of Prosecutor General whose office had a role in pursuing the defendant in first place!

Section 5 of Article 14 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that “Everyone convicted of a crime shall have the right to his conviction and sentence being reviewed by a higher tribunal according to law”.

The Prosecutor General or the Head of Supreme Court do not constitute a “tribunal”. In fact, Iranian Judiciary with the backing of the law makers has created an express lane to the gallows for drug offenders in violation of international laws and Iran’s international obligations.

War on Drug?

Iranian authorities have successfully argued in favour of the death penalty by stating that Iran needs a tough stance against drug trafficking given that its Eastern neighbour, Afghanistan, is the world’s largest producer of illegal opium, making Iran a first and important transit point for trafficking drugs to European countries. In addition, Iran has one of the highest, and by some accounts the highest, rate of drug addiction in the world. Estimates of Iranian adult addicted to drugs range from 2 to 5 million (2-5 percent of the population) . Finally, Iran cites the 3700 soldiers who have been killed and thousands more who have been disabled in its war against drugs .

Iran’s counternarcotic efforts have won praise from such International bodies as United Nations’ Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and have attracted generous funding and support from European countries such as Norway (Ireland stopped such funding in November of 2013 out of concern over the executions ).

On March 11th, 2014, Yury Fedotov, executive director of the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) praised Iran’s anti-drug efforts stating that “Iran takes a very active role to fight against illicit drugs…it is very impressive” .

There are two main reasons why such efforts and praise thereof are misguided. Firstly, one of the principle elements of Iran’s war on drug is “execution therapy”. Islamic Republic has a long history of resorting to execution as panacea for political and security challenges as well as social ills. Drug trafficking and drug use seem like untameable challenges that have afflicted Iranian society, and compromised its social stability. Iran’s response to the problem has been mass execution of small drug dealers. In fact, a look at the past year’s long list of executions shows that most of those hanged were “petty” drug dealers. Most defendants are marginalized members of the society often dealing with poverty and addiction. There are three cases which, in particular, highlight the profile of some of those executed. All three were single mothers who appear to have engaged in drug dealing for not having any other means of supporting their children. Amnesty International, in the Urgent Action issued prior to their executions, described the three women as “Hourieh Sabahi, Leila Hayati and Roghieh Khalaji…believed to be low-ranking members of a larger drug trafficking operation. During their interrogation, they had no access to a lawyer…They had no right to appeal as their sentences were only confirmed by the Prosecutor-General… The women are all mothers of dependent children, currently cared for by relatives. Hourieh Sabahi has four children, one of whom is disabled. Two of them are aged 15 and 13; the ages of the other are unknown. Leila Hayati has a 10-year-old son and Roghieh Khalaji has a 14-year-old son and a 12-year-old daughter. Their husbands are reportedly drug-addicts, either serving life sentences in prison or homeless, and are unable to support their children. The women reportedly turned to drug trafficking as a result of poverty ”.

This brings us to the second reason for such efforts being spurious: it appears that the IR authorities simply pursue, prosecute and punish the small dealers and users while the large cartels and their heads continue to operate with immunity. Furthermore, there are evidences that Islamic Republic or at least some of its most power institutions such as IR Revolutionary Guards are involved in trafficking drugs. A WikiLeaks cable from Azerbaijan revealed that “[t]he Iranian government has repeatedly released convicted Iranian drug smugglers handed over by the [Government of Azerbaijan]…in several cases [Azeri officials] have even caught again Iranian drug smugglers that [they] had previously handed over to [Iran]” .

Given that Azerbaijan serves as the point of transit of heroin from Iran to Europe and has increasingly seen enormous amount of narcotics entering its borders from Iran, such actions by Iranian authorities greatly undermines their claim of fighting drug trafficking.

An ostensible war on drug has practically become a war against some of the most marginalized Iranians. They are mere nuisance to Iranian authorities whose arrest and execution is proudly publicised to win recognition and funding from International Community, and they are loathed by Iranian as they are blamed for ubiquitous drug addiction problem that has afflicted Iranian society.

International community has to urge Iranian authorities to suspend all executions, introduce and enforce laws that would improve the due process for the drug offenders, and change the direction of a war that unfairly targets the most vulnerable members of Iranian society in favour of large narcotic operations. Iran has to opt for rehabilitation and harm reduction in lieu of using noose as a nostrum for the complex drug crisis on its hands. For their part, the United Nations and the European Union members must suspend recognition and funding of Iranian counternarcotic efforts unless Iran upholds its international obligations and implements measures to protect the rights of the defendants to due process and fair legal proceedings.

Siavosh Jalili is a Human Rights activist and member in good standing with Iran Roundtable's task force on "Democracy & Human Rights"